The "Labor" problem

And for my next trick, I'll turn $13 per hour and transform it to less than $3 per hour

Summary -

Employers still struggle with finding workers, despite near record level workforce participation

Small businesses especially struggle to compete for available labor

Families wages are significantly reduced through health, childcare costs

Policies that support family access to health, childcare will do more to address workforce needs than previous efforts to enact punitive social policies

Happy Labor Day - A holiday borne from those lowly workers who dared stand up to noble late 1800s businesses that forced 12 hour shifts, 7 days a week, for low pay, and had little concern about working children as young as 5 for even lower wages.

It’s not that bad nowadays, but the struggles between labor and capital persists. I’ve written and spoken before about this summer’s strike at Frito Lay, and how those workers were mistreated, despite parent company PepsiCo’s CEO-to-employee compensation ratio of 462:1.

Yet, despite a robust post-Covid economy, there biggest complaint seems to be a lack of available workers. The blame from some quarters has been pointed at enhanced federal unemployment benefits that ended this week. But I’m going to let you in on something - I’ve been hearing that same thing for more than 20 years. There’s never been a time in my working life that business has said its satisfied with its applicant pool.

That tells me it’s a chronic problem - and if we can agree it’s a chronic problem, we might all be able to agree that we’d like to fix it. The rub comes in how we chose to address the problem.

Historically, we’ve approached this problem from a perspective the problem rests with people. I’ve heard some argue, essentially, that people are lazy by nature and don’t want to work. As such we’ve deployed punitive measures designed to compel reluctant workers into the labor market. We’ve consistently made it more difficult for displaced workers to get unemployment, we’ve cut food assistance programs, money for child care, and along the way, we’ve created more bureaucratic obstacles to accessing those benefits. That tells me the people in power believe our workforce issues are a “people” problem and policy must be designed to change only behavior.

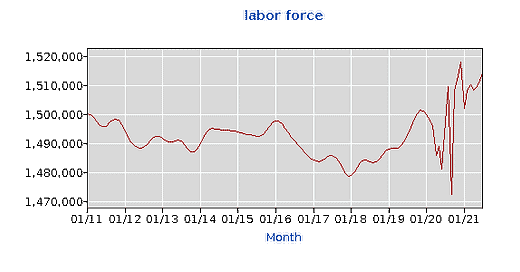

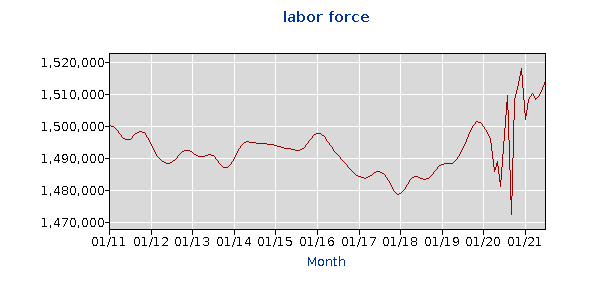

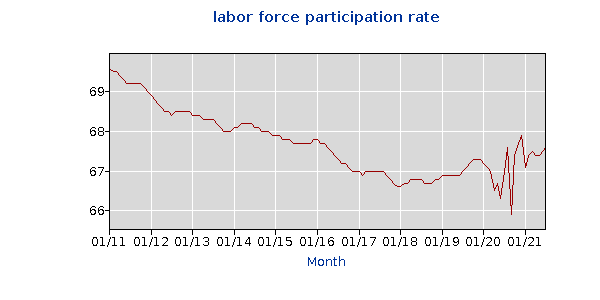

Yet according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, today’s Labor Force Participation Rate is slightly higher today than it was in March 2020, when Covid-19 hit. And that rate is only down 2.1 percent from it’s historical high in the last 20 years.

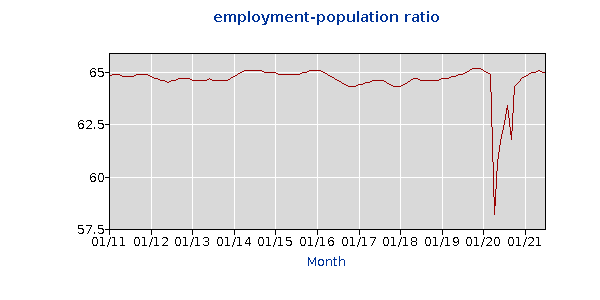

More telling is that the current employment-population ratio of 65 is very near the 20-year historical high of 65.2 in 2019. That means there is a higher rate of working age population currently in the workforce than at almost anytime in the past 20 years. (Here’s a decent definition of employment-population ratio. More than unemployment rate, this provides a more accurate reflection of the number of working age people actively in the labor force).

It’s really pretty simple: In July 2011, there were 1,496,109 people in the Kansas workforce; in July 2021 there were 1,514,522 people in the workforce. Despite the turmoil of the pandemic, there are more people in the workforce today than in almost any time in the past 20 years.

So what’s the problem?

There are a myriad of reasons for that, and there’s no universal way to account for it. It could range from geography, skills gap, an aging workforce, lacking local infrastructure, people leaving the workforce to start a business or stand up “gig” work that often is more flexible to one’s schedule. Below is taken from a McKinsey report on what to expect in 2021.

Disruption creates space for entrepreneurs—and that’s what is happening in the United States, in particular, but also in other major economies. We admit that we didn’t see this coming. After all, during the 2008–09 financial crisis, small-business formation declined, and it rose only slightly during the recessions of 2001 and 1990–91. This time, though, there is a veritable flood of new small businesses. In the third quarter of 2020 alone, there were more than 1.5 million new-business applications in the United States—almost double the figure for the same period in 2019.

It could also be that we’re creating jobs faster than we can find people to fill those jobs. And we’re sure not doing much in Kansas to help encourage people want to move to Kansas - and that’s reflected in the latest census figures. We also complain endlessly about “brain-drain” and how kids leave the state as soon as possible. Yet we yearly see regressive legislative policies that send young people fleeing to places with better quality-of-life, equity, and earning potential.

We have to start talking about real vs effective wages

In Hutchinson it’s anecdotally understood that a job that pays around $13/hour is “pretty good.” At that rate, for a 40-hour week, you’d gross $520 per week, or $27,040 per year. According to BLS, the average weekly wage for Reno County is $764 per week, or $39,728 per year. That equals $19.10/hour on a 40-hour work week. (Remember that this number includes everything from a doctor and CEO to a server making $2.30 an hour. And we have a lot more servers than doctors)

That’s the real wage.

Remember the outrage you felt when you got your first real paycheck as a teenager, and saw how much was held out for taxes? From the day a person starts working, their earnings are sliced and diced in a variety of ways.

The 7.65 percent FICA tax for Social Security and Medicare is taken off the top. If you make around $40,000 you’ll be on the hook for about 12 percent for federal income tax, and 5.25 percent for Kansas income tax. On a $40,000 annual income, that’s about $6,900 combined - but there are exemptions and credits that considerably reduce a family’s tax liability.

The point here is that for us working stiffs, there’s no escape from payroll taxes. No expensive accountants to massage the numbers, no write-offs or loss carryforwards to offset tax liability. If you work a job, the taxes are taken off the top. If we assume even a modest final rate of 5 percent in combined income taxes coupled with the 7.65 percent FICA tax, that $19.10 average wage is reduced by $2.42 (rounded) per hour, to an effective rate of $16.68 per hour.

But if you work and you have children, you’re going to need someone to provide care for your children - and we face several critical issues in this area that are contributing to workforce issues.

The first is that we don’t have enough supply. It’s difficult to find openings - particularly for infant children. This is a problem that’s pervasive across communities of all sizes. I won’t dive too far into this issue now - because it’s big and complex. But I will say that generally, we’ve had an attitude in this country that anyone can care for children - and hence, we’ve not given it proper financial value. Given what we now know about the effects of adequate and affordable childcare on the economy, on society, and on early brain development, we must make this a higher priority.

But the other side of this is that when you do find good childcare, it’s expensive.

According to the most recent market study from the Department of Children and Family Services, the median hourly rate for full-time childcare was $2.36 per hour at child care centers, and $2.13 per hour for a in-home child care center.

That seemed low to me. So I reached out to find out what others were generally paying for childcare. Here’s some of what I got back:

To see the entire message thread, go here. That’s only on Facebook - I also received a number of private messages and emails on the matter.

But what I got from a great amount of public feedback is that childcare costs vary greatly - depending on location, and delivery. But it feels like the average is somewhere around $130/week per child.

Assuming that the average family has two children, that’s $260/week - or $6.5 per hour.

So that $19.10/hour a job that was reduced to at least $16.68 after taxes, is now down to an effective wage of $10.18 per hour after childcare.

But that’s not all the average working family faces! We haven’t even touched on healthcare yet.

According to the Commonwealth Fund, the average Kansas household pays about $3,000 out of pocket between premiums and deductibles for employer-sponsored insurance. I suspect this is also low, but don’t have better evidence to prove it. Anecdotally, I know people avoid care and don’t go to the doctor for needed procedures - even if they have health insurance - because the cost is prohibitive. Families with chronic health conditions certainly pay more. And the fact that most policies have out-of-pocket maxes in the $5,000-$6,000 range tells me that’s the norm. But for the sake of this argument, we’ll assume the $3,000 per year.

That equals $1.44 per hour in out of pocket health care costs. So that same $19.10/hour job, after taxes, child care, and health care, is effectively $8.78/hour, or $18,262/year.

Here’s the math thus far:

Gross pay: 19.10/hour

Taxes: - $2.42/hour

Childcare: - $6.5/hour

Healthcare: - $1.44/hour

Effective wage: $8.74/hour

Now, imagine that those costs remain static at a lower wage - let’s say that “pretty good” Reno County wage of $13/hour.

Gross pay: $13/hour

Taxes: - $2.42/hour (maybe a bit less at this lower wage, but not much)

Childcare: - $6.5/hour

Healthcare: - $1.44/hour

Effective wage: $2.64/hour

When the effective wage is reduced to less than $3.00 per hour, or $5,491/year, families are forced to make decisions about how to spend their time - and working 40 hours a week to give most of their money away is not a sound financial, or family, decision.

We can make judgements all day long about how we think people should behave, but those judgements won’t change the reality we face. You can’t expect people to work when the actual wage they earn is so abysmally low. Over time, that effective wage might rise - for instance when children enter full-time school - but families with young children start out behind the 8-ball financially.

I do want to acknowledge that in some cases, people can work and still qualify for limited benefits that offset the costs of childcare and groceries. But I think there’s enough evidence that it doesn’t adequately address the core issues we face. And I want to be careful to not create the idea that childcare is making a killing from their services. Childcare centers often are supported by churches or community groups because it’s a difficult business to make work, financially. It’s heavily regulated and costly to operate.

Small business faces exceptional challenges

This issue with effective wages is more pronounced in small businesses. Large corporations have the advantage of large amounts of capital, and therefore, can more effectively compete for available labor.

But what of the small operators. The mom-and-pop businesses we claim to love so much? They often can’t afford to provide benefits, nor can they afford to drastically raise wages without having some impact on their business.

I have friends who run small businesses. They are good people, who work hard to keep their business afloat. In Hutchinson, some of those businesses are my favorite places to visit. They, too, are having a tough time finding people to work. But in this, they struggle against the biggest employers in any community, who can offer better benefits and wages.

Smaller businesses generally can’t afford employer-sponsored health coverage. And in many service jobs, the hours are later in the day, or more variable than 9-5 jobs. For those employees, finding child care is a real challenge - as after-hours child care centers are far and few between, and typically charge a premium.

There’s also a social cost I don’t think we consider. We now know that 0-3 are the most critical years of a child’s life. Get it right here, and there are great benefits - higher earnings, less legal trouble, lower teen pregnancy, etc. Get it wrong, and the pays a higher cost on the back in - and extends the cost into another generation.

Investing in systems are good for business and workers

Systems matter. And the system we’re in now benefits the biggest corporations - it ensures that they have the best access to the talent pool through their ability to afford the best benefits.

Meanwhile, mom and pop shops and local businesses struggle to get by, and they can’t find enough employees to stay afloat, or grow.

The solution, to me, is addressing the systemic issues - such as healthcare and childcare. If we don’t find a way to address these, I suspect business and industry will continue to struggle to find the workforces they so need.

I have always questioned why so-called pro-business groups like the Kansas Chamber of Commerce have stood in the way of things like Medicaid Expansion. If they were truly pro-business, and not just pro-big business, they’d be the biggest champions of healthcare and childcare reforms. Because, as I see it, there are three primary approaches we can take:

Maintain the status quo and continue to struggle as we’ve done for at least 20 years.

Raise wages to a level that the effective wage is worth working that provides a decent standard of living

Invest in systems that augment wages, so that even low wage jobs provide a decent standard of living.

In my view, Option 3 is the best - because (I’ll agree with my more conservative friends here) no matter how how we raise the minimum wage, it will always be the floor of the wage structure. I think wages have been stagnant for a long time, and I think they should go up - but we have to acknowledge that there will always be jobs that are low wage relative to higher wages. That is fundamental, and won’t change. But we can create an environment where anyone, working any job at any wage, can thrive in the American economy.

The benefit in this approach is that it wouldn’t benefit just the working poor, but also helps middle income families. That keeps more money in family, local, and national economies.

It also puts small business on the same plane as big business - and will allow them to effectively compete for labor - while allowing individuals the freedom to truly chose their employer. As it is now, a lot of people might rather venture out on their own, or work for a small, local business - but don’t because they can’t afford to be without health insurance or other benefits offered by large corporations.

I think we all instinctively know that something has been wrong for a very long time. We might not have been able to put our finger on it, but we’ve known. I have felt that too. Some people blame government, or immigrants, or politicians. But to me, it seems our systems are primarily built around the aggregation of wealth, and the equation of capital and labor has been out of balance for some time.

These conversations on the structure of our economy often get pegged with easy-to-read labels. That’s great when you’re shopping, but isn’t useful if we’re trying to solve a complex problem. If we truly want to figure out this workforce issue, we’re going to have to consider something different - because we’ve been trying the tax cut/reduced benefit path for years - and yet here we remain, with the same complaints that we’ve heard for more than 20 years.

It’s well past time to accept the reality that policies like Medicaid Expansion and helping families find quality, affordable childcare are pro-business AND pro-worker.

This is great!! Very well said!! Thank you for the wonderful article , hard work, and the breakdown that you did for the community!! I will definitely forward and share this!!

Wow!!