What I've been reading this week

This past week, while listening to a podcast about the goings on in Washington, D.C., a nugget of information struck me that was relatable to the ongoing debate about whether Kansas should, or should not, end the enhanced $300 unemployment benefit so we can “get Kansas back to work.” (It helps if you say that last part louder, and slower, while chewing on a mouthful of money).

Basically, Congressional Republicans countered President Biden’s transportation plan with a scaled-down version that used repurposed Covid-19 relief money - including the extra unemployment money that 20-something Republican governors have rejected.

When I combine the multi-state national effort with the coordinated call in Kansas for ending enhanced unemployment benefits from the Kansas Delegation, the Kansas Chamber et al, and our statehouse leadership, the picture came even clearer into focus.

But I wanted to do some additional research to see if broader reporting on the topic supported my theory.

This article explained a study from JPMorgan Chase that the call to end enhanced benefits was tied to politics, not economics.

But it noted that neither unemployment rates, earnings growth, nor participation levels are driving states to halt jobless aid early. "It therefore looks like politics, rather than economics, is driving early decisions to end these programs," they wrote.

Then I found another interesting study from JPMorgan Chase back in October, that showed how important the first round of federal unemployment benefits - under then President Trump - was to the national economy. The short version is that because of the benefits, unemployed workers both spent and saved more while the benefits were in place - doing exactly what they were designed to do: Support families in crisis and carry the country through economic hardship.

In article after article - in nearly all the data and reporting I looked at on the topic - there’s little concrete connection between the current labor shortage and the federal unemployment benefits.

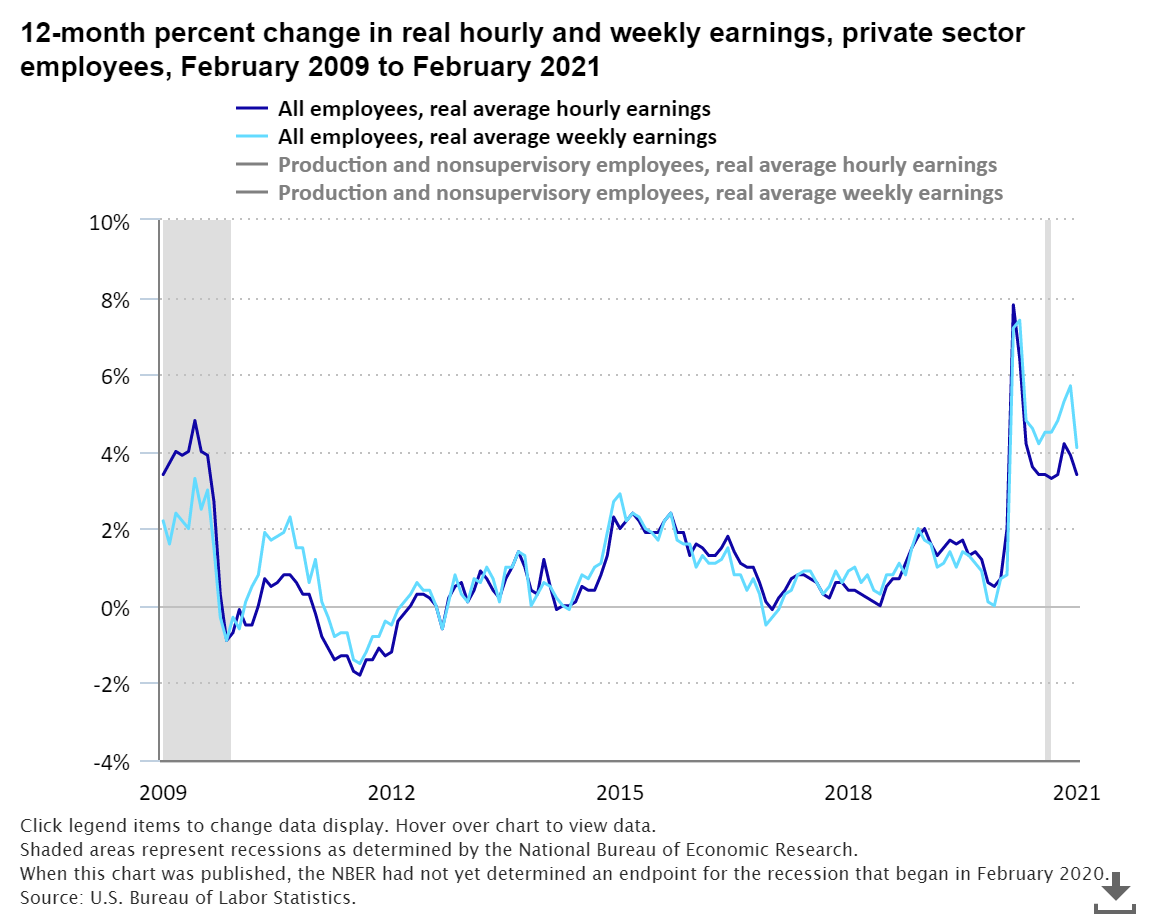

The Economic Policy Institute highlights that the tell-tale sign of a legitimate labor shortage is an increase in wages - and that hasn’t happened in a broad way.

And right now, wages are not growing at a rapid pace. While there are issues with measuring wage growth due to the unprecedented job losses of the pandemic, wage series that account for these issues are not showing an increase in wage growth. Unsurprisingly, at a recent press conference, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell dismissed anecdotal claims of labor market shortages, saying, “We don’t see wages moving up yet. And presumably we would see that in a really tight labor market.”

Now, wages did generally go up a bit in 2020, due to the bottom being knocked out of the wage calculation - because the leisure and hospitality industry suffered the most job losses during the height of the pandemic.

Wages grew largely because more than 80% of the 9.6 million net jobs lost in 2020 were jobs held by wage earners in the bottom 25% of the wage distribution. The exit of 7.9 million low-wage workers from the workforce, coupled with the addition of 1.5 million jobs in the top half of the wage distribution, skewed average wages upward.

A longer lens view of wages is, frankly, depressing, because wages have barely moved in the past decade and haven’t fully recovered from the 2008 greed-induced economic crisis.

And this article from MarketWatch attempted to examine the real reasons people aren’t returning to work. (Hint: It’s not enhanced unemployment).

But a recent poll of 1,000 unemployed workers by CNBC and Morning Consult told a different story. Respondents said the trickle-down effect of job openings had not reached them — at least, not yet. Some 87% said they had not received job offers in the last six months.

What’s more, 65% of those surveyed said unemployment benefits were not a factor in their rejecting a job. Instead, they cited too-low salary (36%), concerns about COVID-19 (35%) and the need to care for family (31%). In fact, 76% of those offered a new position said the proposed wages were lower than their prior job.

There are a number of factors that play into workforce issues - and in some reporting and anecdotally, I’ve heard people nearer to retirement age say they plan to retire early, or scale back their workload. It seemingly turns out that if you get a minute to step out of the rat race, you might decide to not get back in.

Another element lost in this politics-induced rage about federal benefits is that it is currently supporting small business owners who might otherwise have few resources to carry them through this time.

From a CNBC article:

“While Justin Mackey worked to rebuild his locksmith business, the 38-year-old was relying on getting a $420-a-week unemployment check for another four months.

That money was a fraction of what he brought home before the coronavirus pandemic shut down his business in Arkansas, but at least it kept his mortgage and other bills paid. And it allowed him to buy clothes and school supplies for his three young children: Camdyn, 14, Connor, 7, and Charlie, 3.

“It’s better than losing everything,” Mackey said.

The bottom line is that whatever workforce issues we’re facing are not new, and they didn’t arise out of nowhere because a few more families have two nickels to rub together. Even the conservative free-market economic think tank American Institute for Economic Research pointed that out in a February 2019 article.

The statistics are staggering in both their magnitude and breadth. By size, 79 percent of firms performing $50 million or less in work reported having trouble finding craft workers. On the other end of the spectrum, 82 percent of firms that performed $500 million or more in work indicated the same. The difficulties are, furthermore, being felt nationwide: 81 percent of contractors in the West and South, 80 percent in the Midwest, and 77 percent in the Northeast are reporting severe issues procuring labor; in 2017, those numbers ranged from 63 percent to 77 percent…And the crisis extends far beyond construction: in many subsectors of agriculture, home care, transportation, and manufacturing, the same phenomena are being reported. An estimated 8 million people, representing 5 percent of the entire U.S. workforce, are either fleeing or laying low.

America, and Kansas, does have a workforce problem - but it wasn’t born in 2021 and it’s not because a few extra bones are being routed to families. To focus on this one aspect is playing into a political game that’s above our pay grades and doing so fails to authentically examine the issues affecting the labor force and prevents us from talking about real ideas and policies that could actually make a difference for a problem we’ve known has existed for years.

BONUS READING:

Trucker shortage largely due to high turnover because of pay structure, schedules

CEO salaries increased during the pandemic while workers struggled

Post-pandemic compensation varies by industry, flex schedules valued

NEW PODCAST

A friend recommended this to me knowing I’m a fan of John Meacham. It examines America’s waning relationship with facts - particularly in political debate. I’m only on episode 2, but can tell I’m going to love it.

<iframe src="

" width="100%" height="232" frameborder="0" allowtransparency="true" allow="encrypted-media"></iframe>